LEARNING TO SEE

[2002]

Author: Manosh Chowdhury

The advertisement caught my eye. It was a camera of an international company. 'Buy this camera, click, and become a photographer in an instant!' Such a provocative ad., that you itch to become a photographer. But the working photographers, the groundwork of their professional lives isn't so easy to create - even when the international camera companies seem to have the answer. Taking pictures for a living is not new. It is intricately tied up with our colonial history. Visual products of our region, over the last few hundred years, have seen enormous changes from the overt influence of Europe. Among them, photography is a modem medium. It also played a defined role in the colonial structure of governance. it was important for the colonial administration to develop various archives. And photography became a valuable tool for documenting the colonised peoples. Through these links, in the modem post-colonial state, a photograph is a necessity for many reasons, mostly for official purposes - and therefore studio photography has an established niche of its own, in various measures and possibilities.

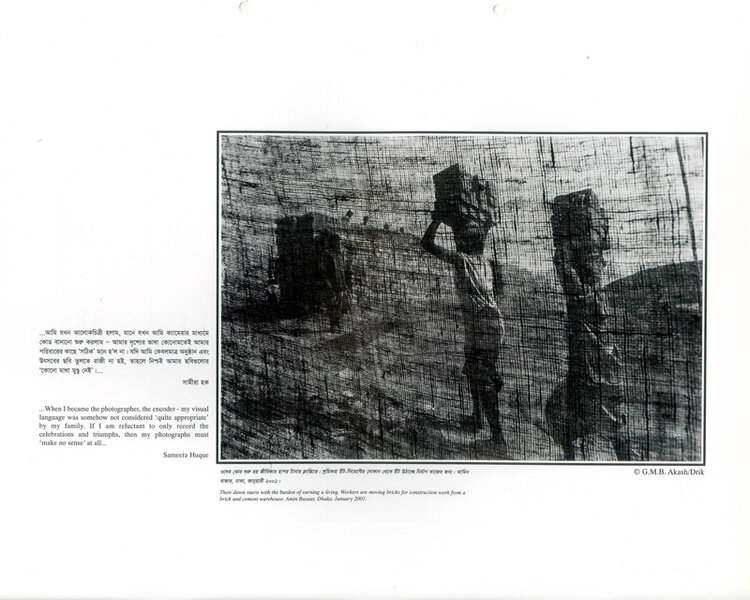

But how are those images being used, and what is the status of a photographer in society? These are issues that demand more than a passing glance. To this day in Bangladesh, despite constant reminding, newspapers are loathed to credit photographers. Even now, photojournalists are few in number, and those working in newspapers find their work receiving teas importance and less pay as a matter of course. This state of affairs is hardly reflected in the progress of film-camera manufacturing multinational companies. They're building on ever stronger foundations, even in Bangladesh. And the photo printing establishments are also busy, with a lot of work at hand. Therefore it appears that photography is over increasing in popularity. The reasons for this are embedded deep in the middle lass world, and them are also clear-cut boundaries for what should be photographed. But that is another discussion altogether. Thousands of photographs are being taken, but people somehow aren't picking up on the importance of photographers. And that is a major paradox.

But how are those images being used, and what is the status of a photographer in society? These are issues that demand more than a passing glance. To this day in Bangladesh, despite constant reminding, newspapers are loathed to credit photographers. Even now, photojournalists are few in number, and those working in newspapers find their work receiving teas importance and less pay as a matter of course. This state of affairs is hardly reflected in the progress of film-camera manufacturing multinational companies. They're building on ever stronger foundations, even in Bangladesh. And the photo printing establishments are also busy, with a lot of work at hand. Therefore it appears that photography is over increasing in popularity. The reasons for this are embedded deep in the middle lass world, and them are also clear-cut boundaries for what should be photographed. But that is another discussion altogether. Thousands of photographs are being taken, but people somehow aren't picking up on the importance of photographers. And that is a major paradox.

That is why Pathshala's founding is so crucial. There are many reasons for it. The first one is easy. There arc only a few places where photography is taught in Bangladesh, and through Pathshala that need has been slightly lessened. In particular, the three-year graduation programme is offering students a tidy, complete, formal education package. Even as universities in Bangladesh have facilities to teach fine arts, within it there are no courses in photography. Secondly, not only photography, but photojournalism is taught at Pathshala. And it is completely independent from all other educational institutions. It is astonishing that even when formal education in journalism is well established, photojournalism studies are marginal in traditional universities. Recently, some development agencies have started showing interest in the media, and courses at photography and journalism have arised from their involvement. But this by no means lessens Pathshala's significance, and only adds to it - which leads us to the third reason.

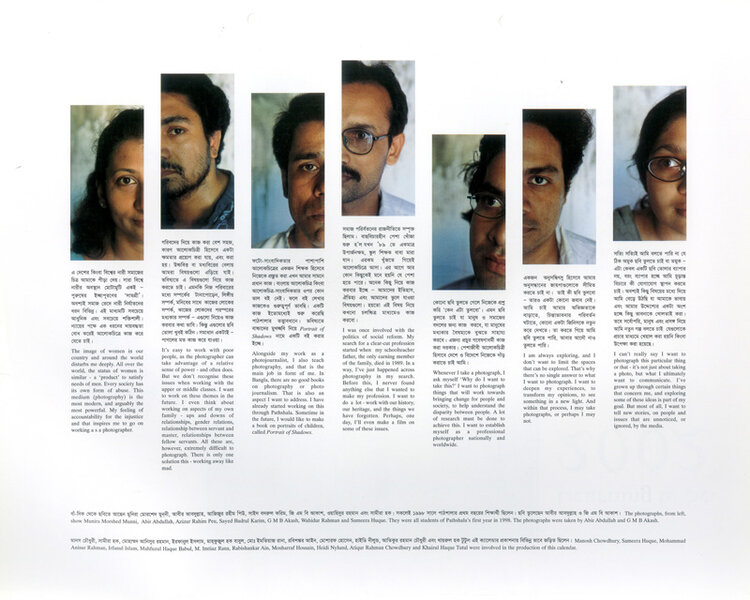

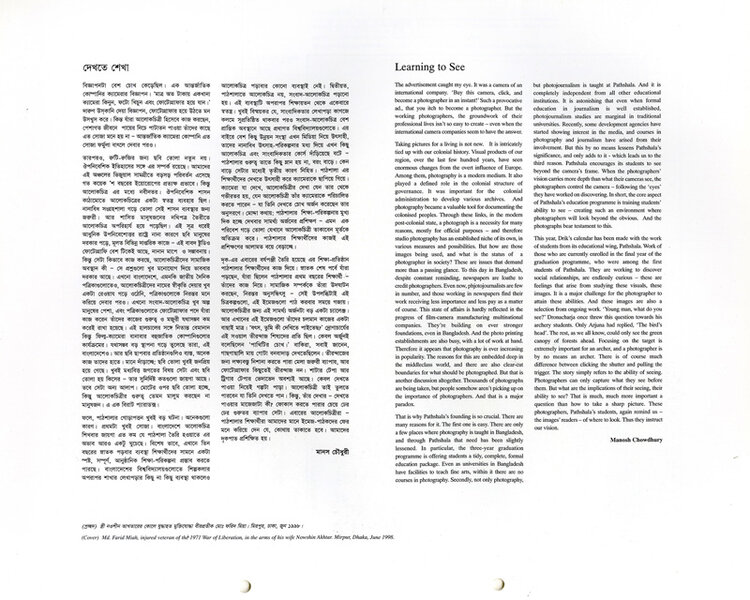

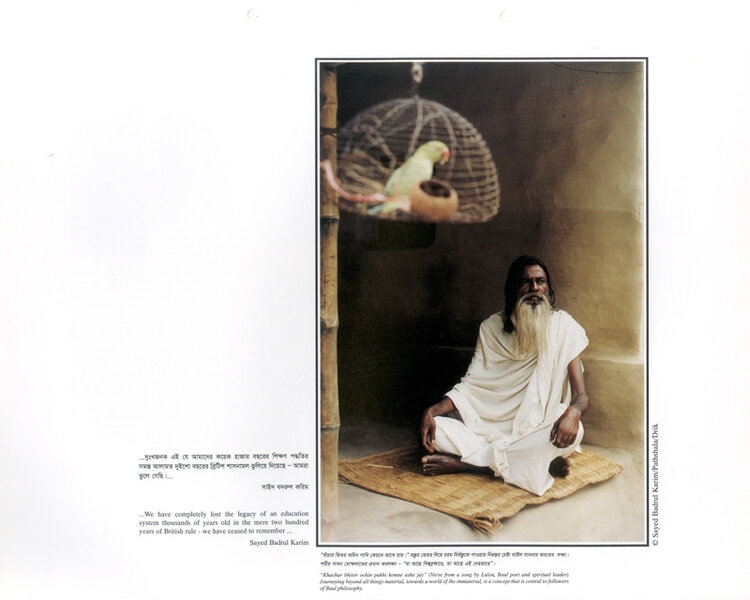

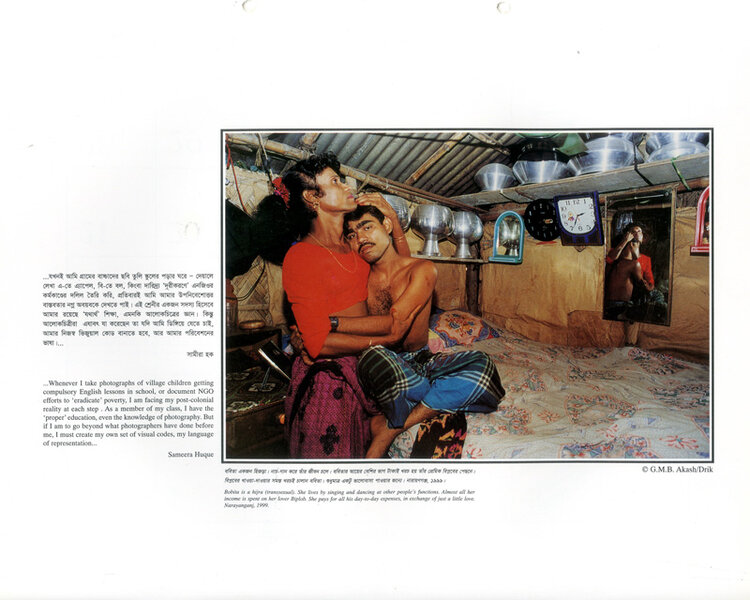

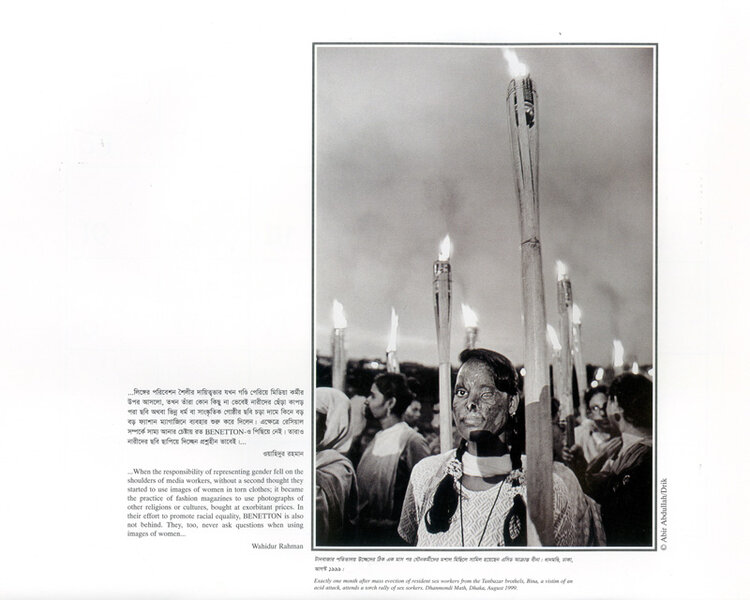

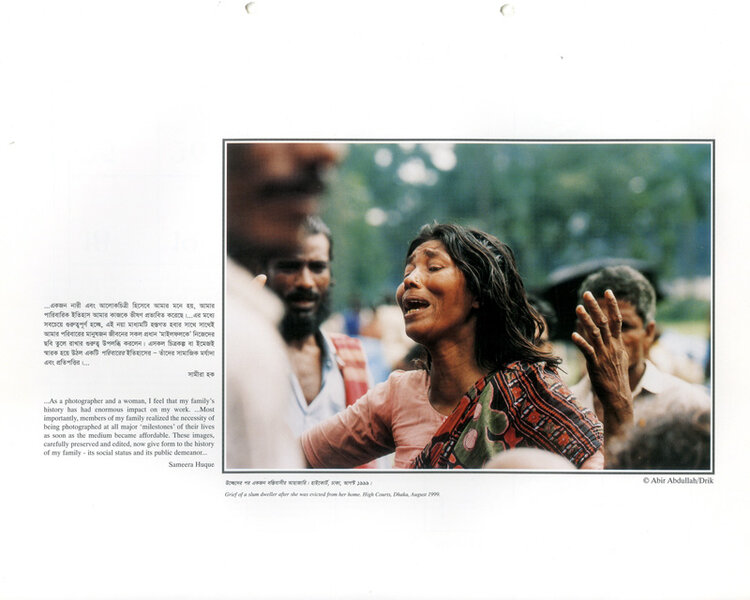

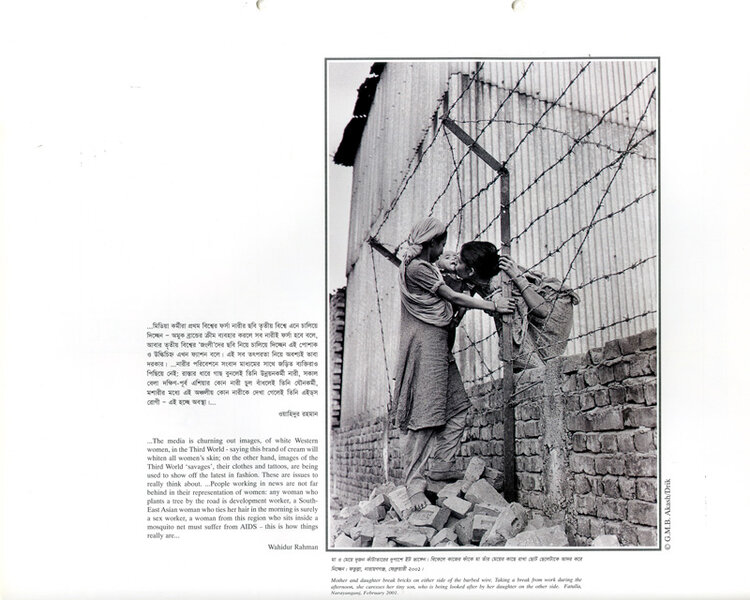

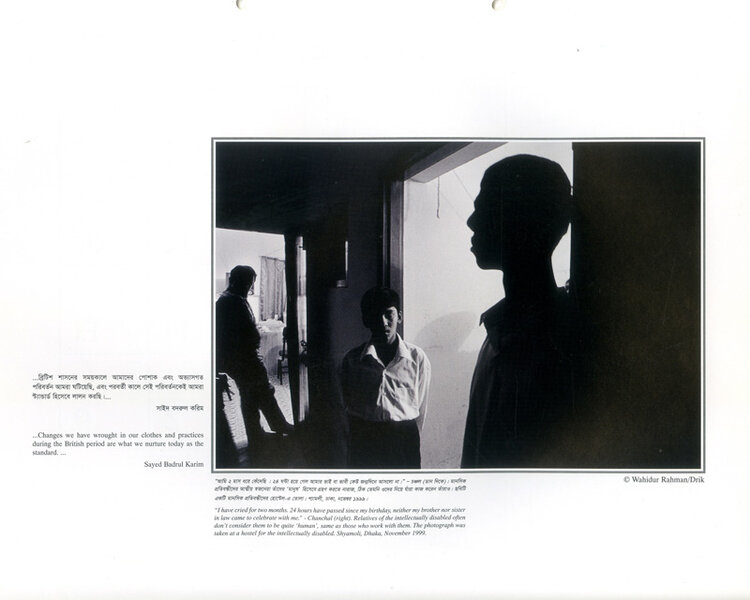

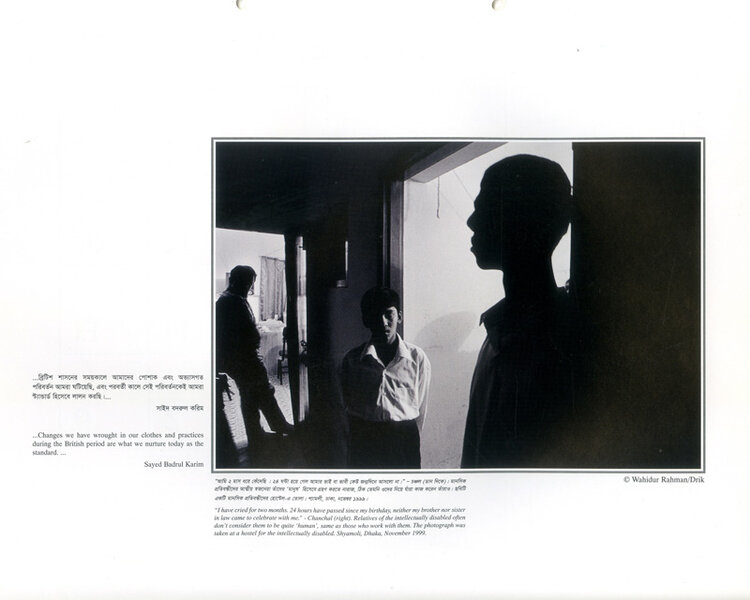

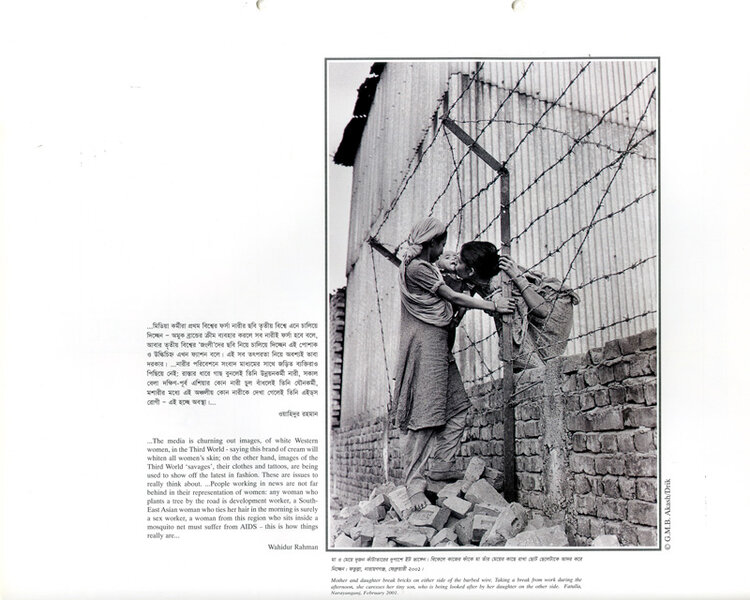

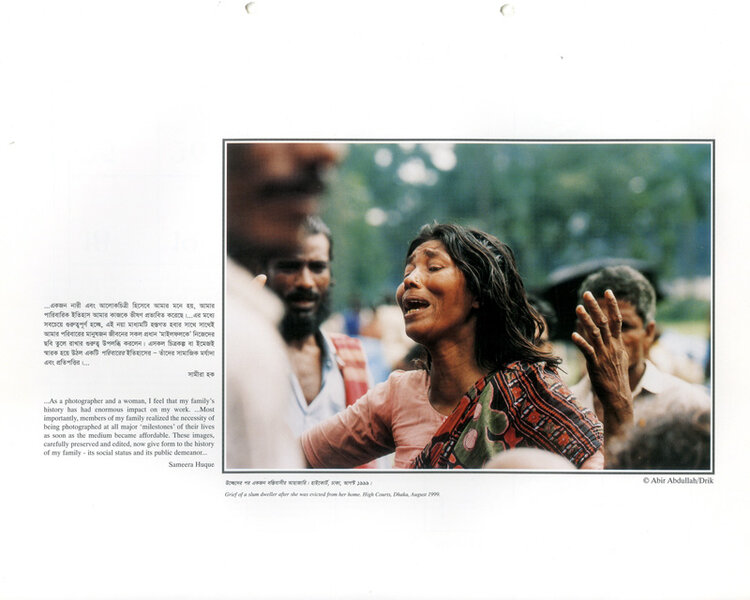

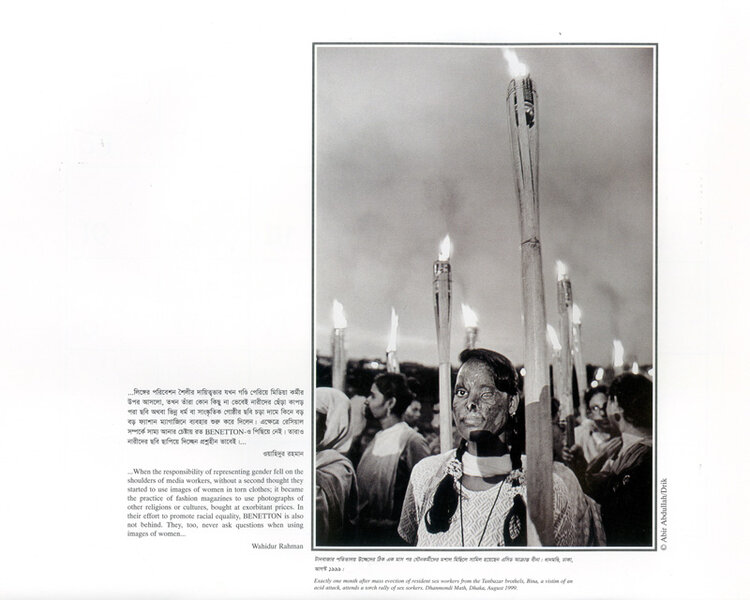

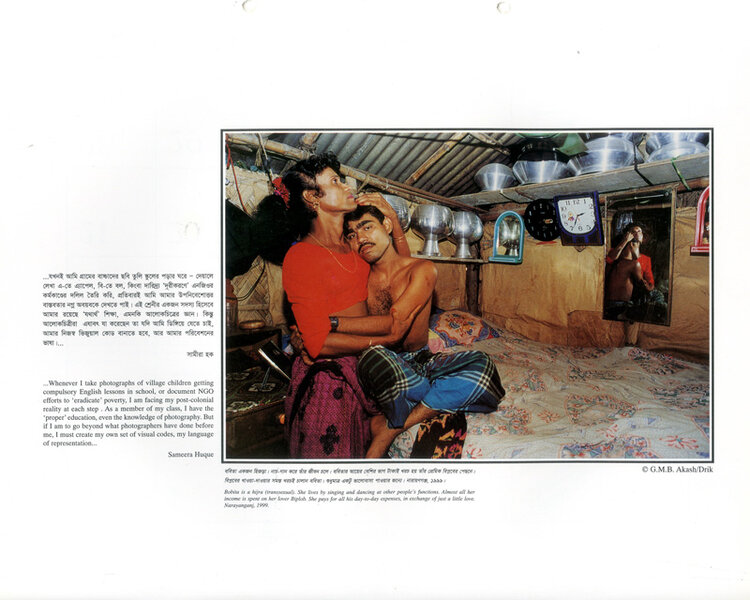

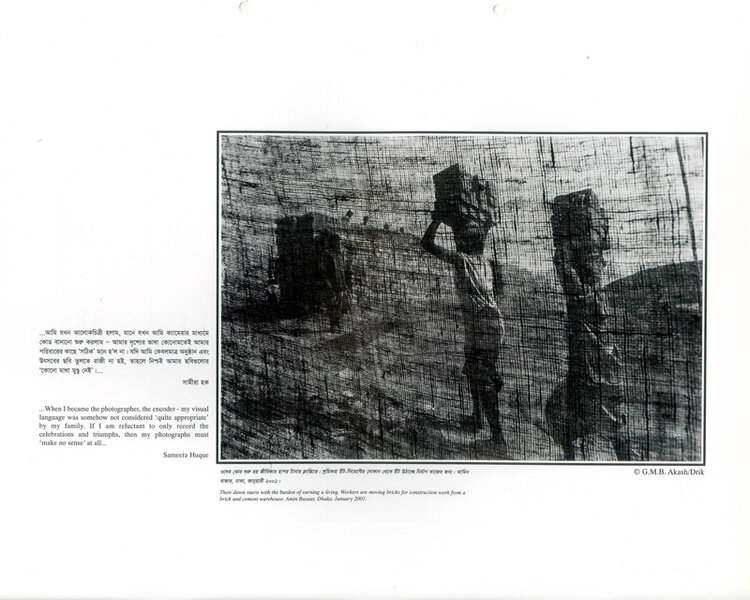

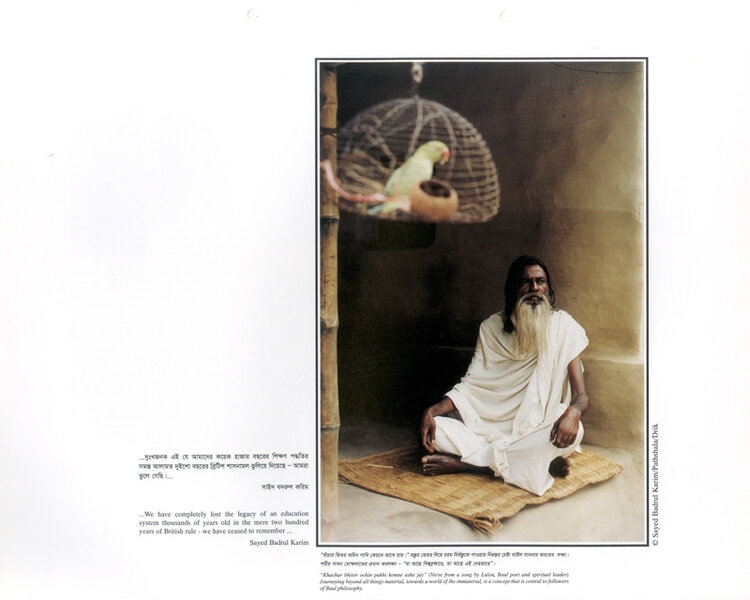

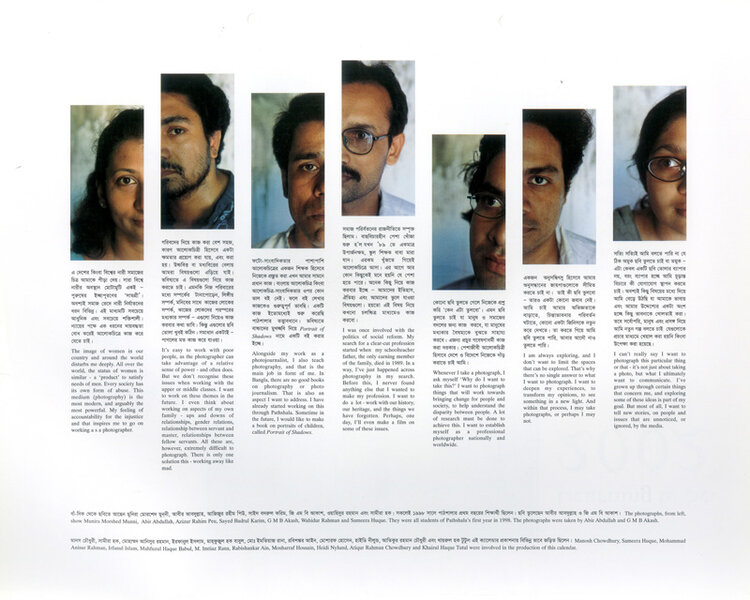

Pathshala encourages its students to see beyond the camera's frame. When the photographers' vision carries more depth than what their cameras see, the photographers control the camera - following the 'eyes' they have worked on discovering. In short, the core aspect of Pathshala's education programme is training students' ability to see - creating such an environment where photographers wilt look beyond the obvious. And the photographs bear testament to this. This year Drik's calendar has been made with the work of students from its educational wing, Pathshala. Work of those who are currently enrolled in the final year of the graduation programme, who were among the first students of Pathshala. They are working to discover social relationships, are endlessly curious - these are feelings that arise from studying these visuals, these images. It is a major challenge for the photographer to attain these abilities. And these images are also a selection from ongoing work. 'Young man, what do you see?' Dronachatja once threw this question towards his archery students. Only Arjuna had replied, 'The bird's head'. The rest, as we all know, could only see the green canopy of forests ahead. Focusing on the target is extremely important for an archer, and a photographer is by no means an archer. There is of course much difference between clicking the shutter and pulling the trigger. The story simply refers to the ability of seeing. Photographers can only capture what they see before them. But what are the implications of their seeing, their ability to sec? That is much, much mom important a question than how to take a sharp picture. These photographers, Pathshala's students, again remind us -the images' readers-of where to look. Thus they instruct our vision.