Golam Kasem Daddy: The Beloved Name

/ Momena Jalil

Golam Kasem Daddy - a name that stands the test of time, like silver halide fixed in the glass plate of some other era. The majority of his photographs have vanished like undeveloped film that was exposed to light. The images are lost forever in the folds of time, by the hands of selfish, careless people who had access to him. He was a man who had lived 104 years and tried his best to save and document his works during that time, but regrettably, only few have survived.

I had the honor and privilege of making the final inventory of the known archived work of Golam Kasem Daddy, while I was working as the Head of then Drik Picture Agency (Drik).

I am a photographer, and that is the most important identity to me. But during my time at Drik, I had the opportunity to handle many outstanding photographers' works. I cannot ever imagine expressing what it feels like to have full access to legendary photographers’ works. And one of the most breathtaking was the archive of Golam Kasem Daddy.

Golam Kasem Daddy was a name which echoed like a murmur; a beloved mystery waiting to unfold. I have never seen nor met Daddy; in fact, he passed away the year I started photography. But with time I understood he was the uncontested Guru of Bangladeshi photographers. I have not met a photographer who does not love him unconditionally. A pioneer who dedicated his outstanding life to photography; his life’s core revolved around it. He was not only a photographer; he was a teacher, a mentor, a lighthouse that never hesitated to show others the way. A deep love and respect developed in my heart for this undisputed Guru of Bangladeshi photography; it was something that I inherited from my seniors.

I still get goosebumps when I think about the first time I held the glass plate negatives of Daddy. They were the most mesmerizing things I had ever seen, looking as beautiful as the day they were developed. Glass negatives: I had heard about them, read about them but never seen them in real time with my own eyes. And ones which were almost a century old, at that. They survived wars, earthquakes, and the evil intent of human beings, to tell the 104 years saga of a brave man, whose love for photography never died.

Whatever amount of work is in this archive, is the only one known to be well documented and accessible still. Many of his negatives have gotten stolen or destroyed, as mentioned in a letter written on 29.11.95 to Major Yusuf Haroon (Retd). Daddy wrote, ‘Nowadays, I forget many things. I have forgotten about taking your and Lipi’s photos. Most of my negatives are ruined by damp, by white ants and by my possible helpers. I do not know if the negatives exist. If they do, I shall try to print.’ This was written when he was 101 years old.

There are rumors that some of his works do exist privately, but sadly with time these works are decaying in isolation with no one coming forward. As Daddy has no legal heir till date, no one can legally take action either. If there is no proof of kin, it will be hard to prove that it is his work. It breaks my heart to think that somewhere, some greedy, selfish people are keeping such treasure from the world; it is such an injustice to Daddy himself. Daddy started photography from 1912 and continued till his death in 1998. Imagine: 86 years of work and just a handful is left. In his own words he said, ‘By nature, I am averse to publicizing myself. Consequently in my long photographic life, though I have taken thousands of pictures, I have rarely participated in photo contests and exhibitions.’ (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90). Daddy sold his first photograph at the age of 98, for Drik’s 1991 calendar.

My main focus is on Daddy’s archive at Drik. Drik has 165 negatives, of which 25 are glass negatives; others are medium format and 135mm negatives. There are some letters, a short autobiography named ‘A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life’, and a handwritten draft of his book ‘SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY’. When I went through his letters and written materials, it felt like I was there at his 73 Indira Road, Dhaka-1215 home, captured in a black & white photograph on a winter morning, frozen in time listening to him. Daddy had an excellent command of English; all the written material is in that language. He had a sublime sense of humor and even in his old age, his handwriting was beautiful and controlled.

In his short autobiography Daddy wrote about his birth, the loss of his mother, and the interesting story of how he started photography. ‘I was born at Jalpaiguri (Bengal) in 1894 under tragic circumstances. My father was moving with his family in primitive bullock carts to join his new station of posting, when I was born at the foot of the Himalayas where snow was falling thick and fast. My mother gave birth to me, and died shortly afterwards, as no help was available.

‘I began photography in 1912 to which I was very unexpectedly initiated. One day a Christian friend of mine tried to take some photos with his newly purchased Box camera, but failed. Somehow or other, I got the impulse to try myself, and curiously enough, I was a little successful. Thus began my photography.’ (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90)

There is a lot of information on Daddy's professional and personal life. There are books written about him: it is common knowledge that he was a short story writer, but photography was his hobby and his passion. He was the first Muslim photographer in this region (from British India, India, East Pakistan and finally Bangladesh) to knowledge. He served in the First World War, where he worked as a Deputy Registrar, Land. Photography was never his profession, that is why one can only imagine what kind of passion and dedication he had for photography to have done such incredible work. He cherished it for 86 long years against all odds, till his last breath.

Daddy came from a different era; in his own words he explains: ‘In those days amateur photographers were very rare. There were, of course, some professional photographers, but they liked to keep their knowledge secret, and did not divulge it to others. So, there were none to help but there were many to discourage. Under these difficulties, I had to proceed with my hobby. Naturally, there was much loss of time, loss of money and loss of energy. There were tremendous disappointments and small successes.’ (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90)

I had the honor and privilege of making the final inventory of the known archived work of Golam Kasem Daddy, while I was working as the Head of then Drik Picture Agency (Drik).

I am a photographer, and that is the most important identity to me. But during my time at Drik, I had the opportunity to handle many outstanding photographers' works. I cannot ever imagine expressing what it feels like to have full access to legendary photographers’ works. And one of the most breathtaking was the archive of Golam Kasem Daddy.

Golam Kasem Daddy was a name which echoed like a murmur; a beloved mystery waiting to unfold. I have never seen nor met Daddy; in fact, he passed away the year I started photography. But with time I understood he was the uncontested Guru of Bangladeshi photographers. I have not met a photographer who does not love him unconditionally. A pioneer who dedicated his outstanding life to photography; his life’s core revolved around it. He was not only a photographer; he was a teacher, a mentor, a lighthouse that never hesitated to show others the way. A deep love and respect developed in my heart for this undisputed Guru of Bangladeshi photography; it was something that I inherited from my seniors.

I still get goosebumps when I think about the first time I held the glass plate negatives of Daddy. They were the most mesmerizing things I had ever seen, looking as beautiful as the day they were developed. Glass negatives: I had heard about them, read about them but never seen them in real time with my own eyes. And ones which were almost a century old, at that. They survived wars, earthquakes, and the evil intent of human beings, to tell the 104 years saga of a brave man, whose love for photography never died.

Whatever amount of work is in this archive, is the only one known to be well documented and accessible still. Many of his negatives have gotten stolen or destroyed, as mentioned in a letter written on 29.11.95 to Major Yusuf Haroon (Retd). Daddy wrote, ‘Nowadays, I forget many things. I have forgotten about taking your and Lipi’s photos. Most of my negatives are ruined by damp, by white ants and by my possible helpers. I do not know if the negatives exist. If they do, I shall try to print.’ This was written when he was 101 years old.

There are rumors that some of his works do exist privately, but sadly with time these works are decaying in isolation with no one coming forward. As Daddy has no legal heir till date, no one can legally take action either. If there is no proof of kin, it will be hard to prove that it is his work. It breaks my heart to think that somewhere, some greedy, selfish people are keeping such treasure from the world; it is such an injustice to Daddy himself. Daddy started photography from 1912 and continued till his death in 1998. Imagine: 86 years of work and just a handful is left. In his own words he said, ‘By nature, I am averse to publicizing myself. Consequently in my long photographic life, though I have taken thousands of pictures, I have rarely participated in photo contests and exhibitions.’ (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90). Daddy sold his first photograph at the age of 98, for Drik’s 1991 calendar.

My main focus is on Daddy’s archive at Drik. Drik has 165 negatives, of which 25 are glass negatives; others are medium format and 135mm negatives. There are some letters, a short autobiography named ‘A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life’, and a handwritten draft of his book ‘SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY’. When I went through his letters and written materials, it felt like I was there at his 73 Indira Road, Dhaka-1215 home, captured in a black & white photograph on a winter morning, frozen in time listening to him. Daddy had an excellent command of English; all the written material is in that language. He had a sublime sense of humor and even in his old age, his handwriting was beautiful and controlled.

In his short autobiography Daddy wrote about his birth, the loss of his mother, and the interesting story of how he started photography. ‘I was born at Jalpaiguri (Bengal) in 1894 under tragic circumstances. My father was moving with his family in primitive bullock carts to join his new station of posting, when I was born at the foot of the Himalayas where snow was falling thick and fast. My mother gave birth to me, and died shortly afterwards, as no help was available.

‘I began photography in 1912 to which I was very unexpectedly initiated. One day a Christian friend of mine tried to take some photos with his newly purchased Box camera, but failed. Somehow or other, I got the impulse to try myself, and curiously enough, I was a little successful. Thus began my photography.’ (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90)

There is a lot of information on Daddy's professional and personal life. There are books written about him: it is common knowledge that he was a short story writer, but photography was his hobby and his passion. He was the first Muslim photographer in this region (from British India, India, East Pakistan and finally Bangladesh) to knowledge. He served in the First World War, where he worked as a Deputy Registrar, Land. Photography was never his profession, that is why one can only imagine what kind of passion and dedication he had for photography to have done such incredible work. He cherished it for 86 long years against all odds, till his last breath.

Daddy came from a different era; in his own words he explains: ‘In those days amateur photographers were very rare. There were, of course, some professional photographers, but they liked to keep their knowledge secret, and did not divulge it to others. So, there were none to help but there were many to discourage. Under these difficulties, I had to proceed with my hobby. Naturally, there was much loss of time, loss of money and loss of energy. There were tremendous disappointments and small successes.’ (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90)

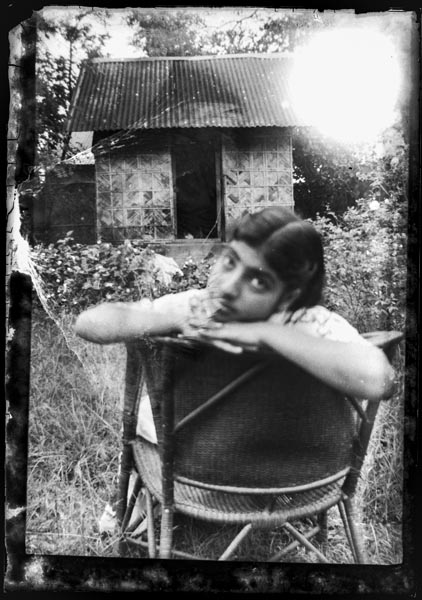

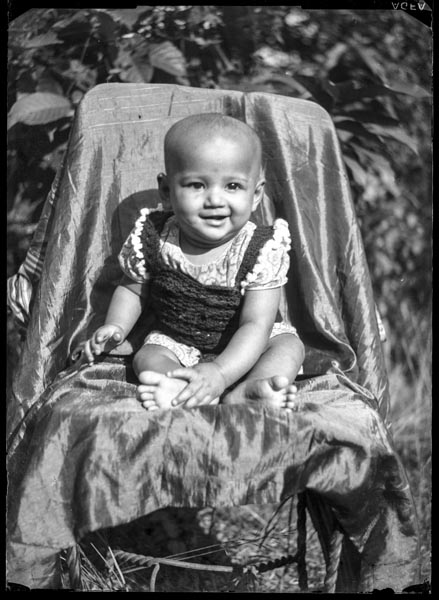

The majority of Daddy’s negatives were in envelopes with handwritten information on them: his earliest negative in the archive is a glass negative dated back to 1918 taken via box camera. (Captioned: Girl in chair, Howrah. 1918) There is a wishful longing in the girl’s expression as she looks back at the camera. A tiny kitten can be seen at the doorway of the house behind; and altogether - it gives off a feeling of home and comfort.

Girl in chair, Howrah. 1918. (Box Camera) Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

‘Portraits – pictures of a person should not be taken in direct sun but in diffused light, otherwise it will be contrasty and without details. Take a close up photo and see that the face looks natural. Effort should be made to have the sitter in a good mood. Use a large stop to make unimportant things hazy.

‘Background – when the background of a subject seems unsatisfactory, a piece of paper or cloth of necessary size and of neutral colour may be used. The articles may be fixed in bamboo or wood for use. Neutral colour means grey or slate.’ (SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Golam Kasem Daddy)

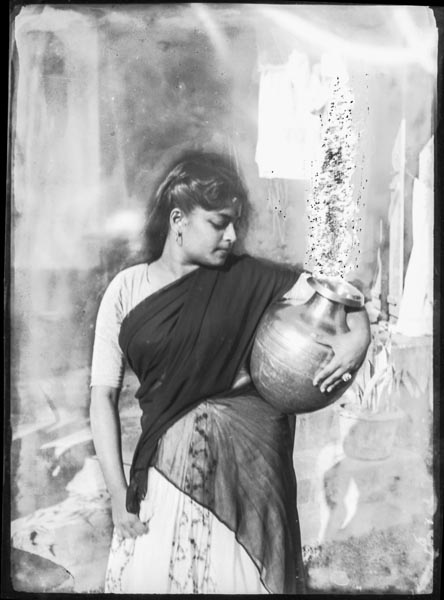

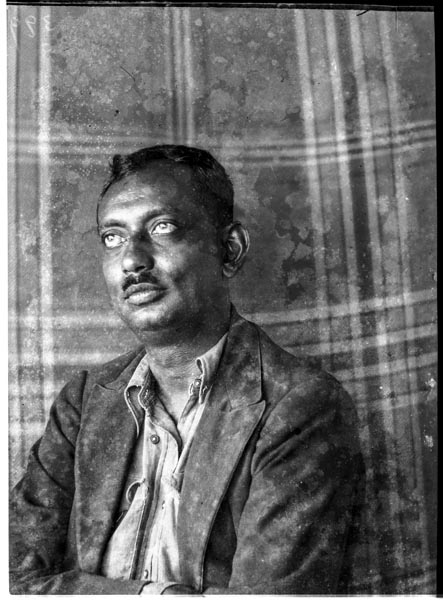

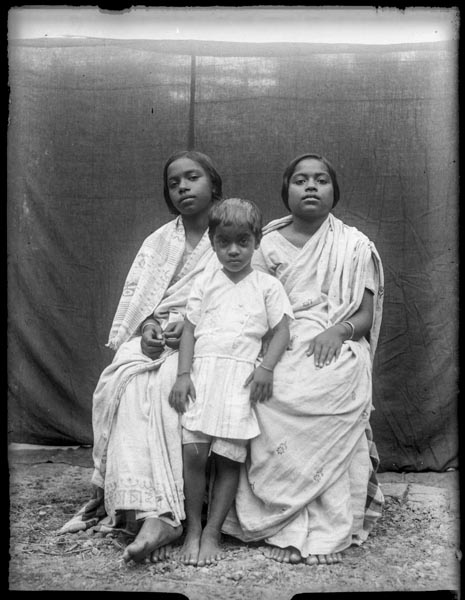

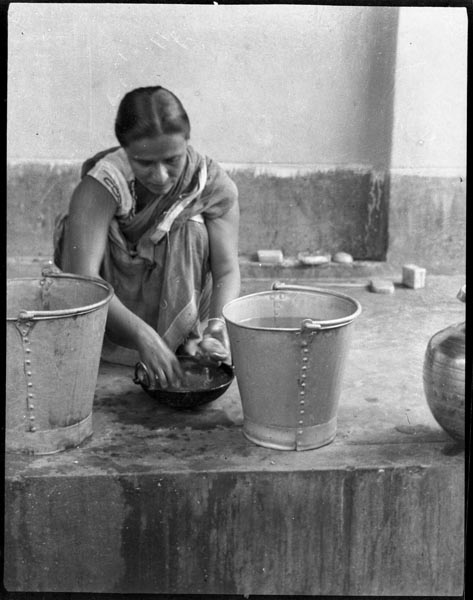

This set which is at Drik reveals his strength and skill in portraiture. Included are No.1, (My colleague, 1935.)

No. 2, (The pitcher, Dhaka. 1952.) No. 3, (A young lady, 1924.) No. 4, (A close-up portrait. 1922) No. 5, (Three sisters, Midnapore. 1925) and No. 6 (Sisters and Brother, Howrah. 1923.) These 6 photographs are testimony to the aforementioned skill. When you see these images, they captivate you, and you discover how profound Daddy’s ability with composition was and how much he was able to bewitch his audience. The fact that he was self-taught and had limitations due to the technology of that era, did not undermine his work, even an atom. Everything about these photographs, the makeshift backgrounds, the use of the natural sunlight - was of the professional level. But the most enchanting part are the expressions of the people in the photographs. You can feel their emotions; how naturally they pose for the camera, completely at ease. And the total praise for this goes to the photographer. None of these people here are alive now but you can feel the life echoing out of these photographs.

‘Background – when the background of a subject seems unsatisfactory, a piece of paper or cloth of necessary size and of neutral colour may be used. The articles may be fixed in bamboo or wood for use. Neutral colour means grey or slate.’ (SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Golam Kasem Daddy)

This set which is at Drik reveals his strength and skill in portraiture. Included are No.1, (My colleague, 1935.)

No. 2, (The pitcher, Dhaka. 1952.) No. 3, (A young lady, 1924.) No. 4, (A close-up portrait. 1922) No. 5, (Three sisters, Midnapore. 1925) and No. 6 (Sisters and Brother, Howrah. 1923.) These 6 photographs are testimony to the aforementioned skill. When you see these images, they captivate you, and you discover how profound Daddy’s ability with composition was and how much he was able to bewitch his audience. The fact that he was self-taught and had limitations due to the technology of that era, did not undermine his work, even an atom. Everything about these photographs, the makeshift backgrounds, the use of the natural sunlight - was of the professional level. But the most enchanting part are the expressions of the people in the photographs. You can feel their emotions; how naturally they pose for the camera, completely at ease. And the total praise for this goes to the photographer. None of these people here are alive now but you can feel the life echoing out of these photographs.

(1)

My colleague, Dhaka. 1935. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(1)

My colleague, Dhaka. 1935. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(2)

The pitcher, Dhaka. 1952. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(2)

The pitcher, Dhaka. 1952. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(3)

Happy girl, Dhaka. 1957. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(3)

Happy girl, Dhaka. 1957. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(4)

A close-up portrait. 1922. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(4)

A close-up portrait. 1922. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(5)

Three sisters, Midnapore. 1925. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(5)

Three sisters, Midnapore. 1925. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(6)

Sisters and Brother, Howrah. 1923. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(6)

Sisters and Brother, Howrah. 1923. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

‘Landscape – these pictures of outdoor scenes should be taken in the afternoon when shadows are long, which help to give a feeling of depth. The scene should be composed suitably so that it looks beautiful. A yellow filter is necessary for improving tones, particularly when there is sky with a subject.’ (SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Golam Kasem Daddy)

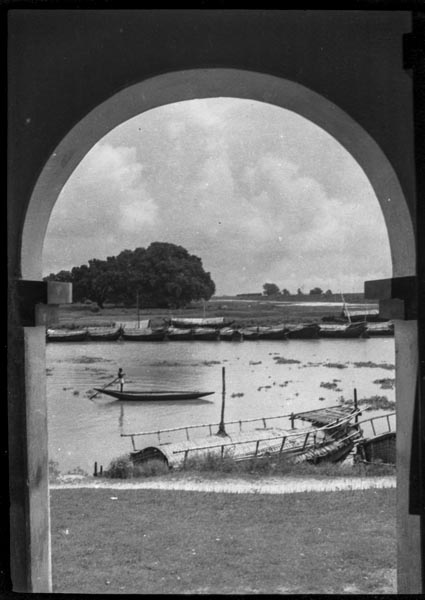

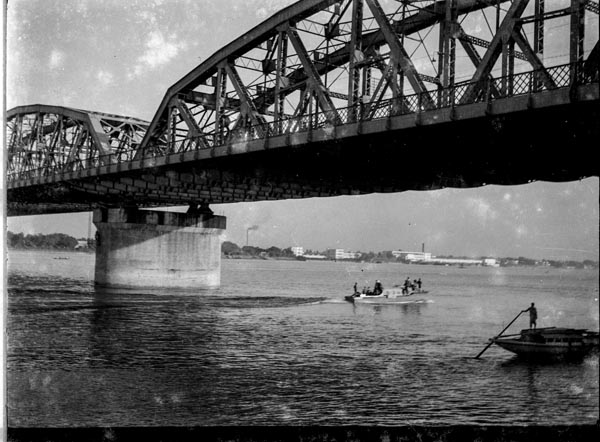

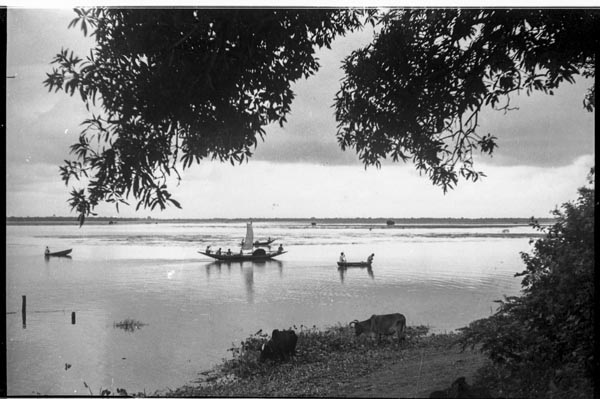

What I find about Daddy’s landscapes are his use of layers: he makes a simple view into an art piece. Let us talk about No.7, (Sentinels, Dhaka. 1961.) The caption itself speaks of two soldiers guarding the dramatic sky. This photograph paints a very surreal aura. On the other hand, No. 10, (Outing on Buriganga. 13.8.78) is of a totally different mood: it is peaceful and soulful at the same time. No. 8, (River scene through Arch, Dhaka. 1952.) is very symmetric, like a doorway to another time. No. 9, (Bridge, Bally Bridge. 1922.) is a photograph of a rail-cum-road bridge over the Hooghly River in West Bengal, India. The interesting fact is that many images of the bridge are there but this one taken in 1922 is special due to its compositional perfection.

What I find about Daddy’s landscapes are his use of layers: he makes a simple view into an art piece. Let us talk about No.7, (Sentinels, Dhaka. 1961.) The caption itself speaks of two soldiers guarding the dramatic sky. This photograph paints a very surreal aura. On the other hand, No. 10, (Outing on Buriganga. 13.8.78) is of a totally different mood: it is peaceful and soulful at the same time. No. 8, (River scene through Arch, Dhaka. 1952.) is very symmetric, like a doorway to another time. No. 9, (Bridge, Bally Bridge. 1922.) is a photograph of a rail-cum-road bridge over the Hooghly River in West Bengal, India. The interesting fact is that many images of the bridge are there but this one taken in 1922 is special due to its compositional perfection.

(7)

Sentinels, Dhaka. 1961. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(7)

Sentinels, Dhaka. 1961. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(8)

River scene through Arch, Dhaka. 1952. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(8)

River scene through Arch, Dhaka. 1952. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(9)

Bridge, Bally Bridge. 1922. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(9)

Bridge, Bally Bridge. 1922. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(10) Outing on Buriganga. 13.8.78. Negative. ©

Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(10) Outing on Buriganga. 13.8.78. Negative. ©

Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

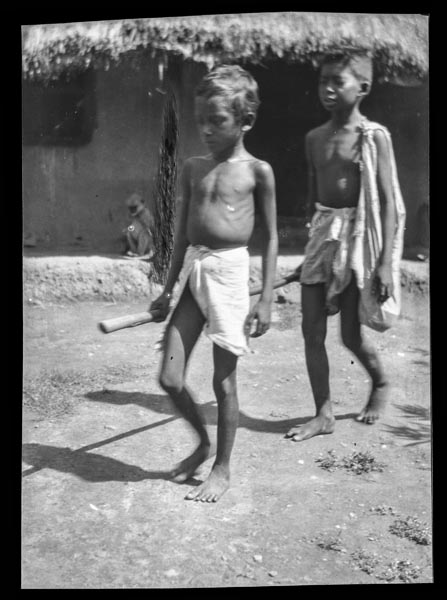

‘Children- they should be taken when playing or doing some interesting work. Otherwise, they will lose their naturalness. It is advisable to make friends with them before taking their pictures. A low view point is suitable.’ (SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Golam Kasem Daddy)

Daddy was inspired by female photographer Edna Larange’s photographs of children. Sadly her works are not available at present. No. 11, (Caption: Her first dance, Midnapore. 1926) delivers a very lively image of children of a time we know little about; and No. 13, (Caption: Playful children, Midnapore. 1926) does the same whilst providing a cultural tour of the early 1900s. No. 14, a picture without caption or date that is likely of the same time period because it was taken on a glass negative, reveals that Daddy had a special charisma with children. Yet, No. 12 (Caption: Blind beggar, Midnapore. 1928.) shows another side of Daddy. His subjects were mostly people of a certain class, people he knew, but this particular photograph pushed him out of his comfort zone. However, there is no disrespect toward his unconventional subject as he photographs the blind beggar with the background where a monkey sits.

Daddy was inspired by female photographer Edna Larange’s photographs of children. Sadly her works are not available at present. No. 11, (Caption: Her first dance, Midnapore. 1926) delivers a very lively image of children of a time we know little about; and No. 13, (Caption: Playful children, Midnapore. 1926) does the same whilst providing a cultural tour of the early 1900s. No. 14, a picture without caption or date that is likely of the same time period because it was taken on a glass negative, reveals that Daddy had a special charisma with children. Yet, No. 12 (Caption: Blind beggar, Midnapore. 1928.) shows another side of Daddy. His subjects were mostly people of a certain class, people he knew, but this particular photograph pushed him out of his comfort zone. However, there is no disrespect toward his unconventional subject as he photographs the blind beggar with the background where a monkey sits.

(11)

Her first dance, Midnapore. 1926. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(11)

Her first dance, Midnapore. 1926. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(12)

Blind beggar, Midnapore. 1928. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(12)

Blind beggar, Midnapore. 1928. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(13)

Playful children, Midnapore. 1926. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(13)

Playful children, Midnapore. 1926. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(14)

No caption. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(14)

No caption. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

‘Flowers – These should also be taken in diffused light. A filter will correct and improve tones. A background should be used to isolate the subject from unimportant surroundings. A single flower may require to be taken from a close distance, and with some cameras a close up lens will be necessary.’ (SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Golam Kasem Daddy)

No. 16, (Roses, Dhaka. 1922) and No. 15, (Flower, Dhaka. 1950) are photographs taken 28 years apart that show the journey of a photographer. Though, I find the one taken in 1922 using a glass negative more captivating. But it must be kept in mind that there is a gap of several years where we do not have any photographs taken by Daddy; perhaps some of his best works remain missing.

No. 16, (Roses, Dhaka. 1922) and No. 15, (Flower, Dhaka. 1950) are photographs taken 28 years apart that show the journey of a photographer. Though, I find the one taken in 1922 using a glass negative more captivating. But it must be kept in mind that there is a gap of several years where we do not have any photographs taken by Daddy; perhaps some of his best works remain missing.

(15)

Flower, Dhaka. 1950. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(15)

Flower, Dhaka. 1950. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(16)

Roses, Dhaka. 1922. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(16)

Roses, Dhaka. 1922. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

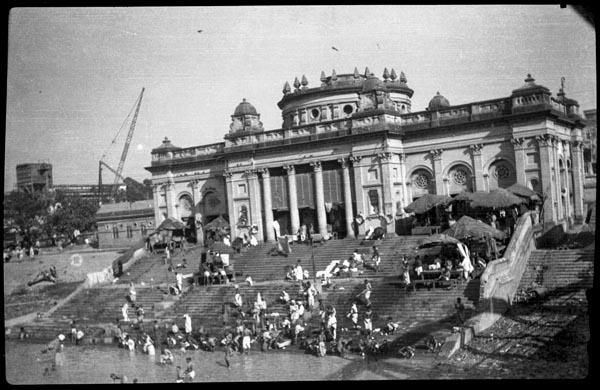

‘Streets and Building – These are subjects for bright sun. This will produce necessary light and shadow to give the picture depth and contrast. A street without traffic may be taken but to make it interesting and attractive further, a figure or two may be placed at the proper place. When there is traffic, street pictures should be taken from a high angle to separate the vehicle from one another and make the scene more interesting.

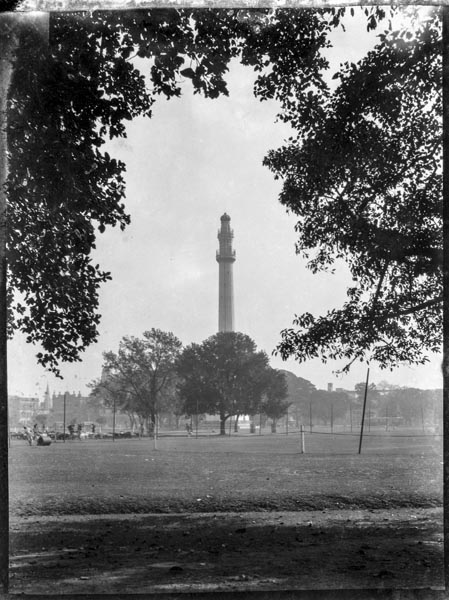

‘Buildings should not be taken from the dead front but from an angle to give the picture light and shade and depth also as already mentioned. It is better to frame a building in an arch or branch of a tree, which will make the picture much more attractive.’ (SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Golam Kasem Daddy)

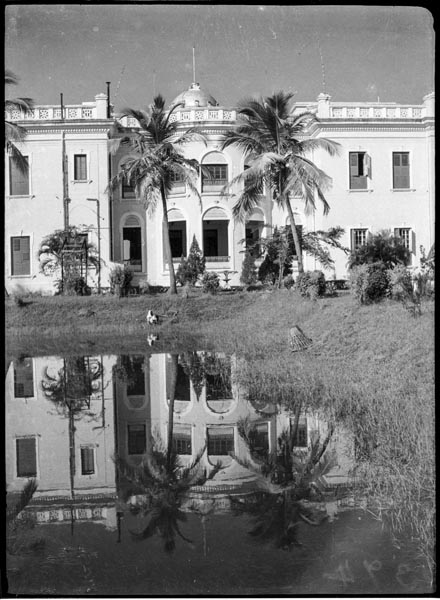

No. 17, (Street view, Calcutta. 1921) is one of the two photographs in city scape. I find this one to be of strong perspective. No. 18 (A crowd of bathers. 1922) is also taken with great care: both of these photographs give particular attention to details. Then No. 19, (Ratha Jatra Car. 1929), No. 20, (Calcutta. 1932) and No.21, (Cats Palace reflections, Mahishadal) show Daddy’s unique ability to use trees and nature to compliment manmade structures.

‘Buildings should not be taken from the dead front but from an angle to give the picture light and shade and depth also as already mentioned. It is better to frame a building in an arch or branch of a tree, which will make the picture much more attractive.’ (SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Golam Kasem Daddy)

No. 17, (Street view, Calcutta. 1921) is one of the two photographs in city scape. I find this one to be of strong perspective. No. 18 (A crowd of bathers. 1922) is also taken with great care: both of these photographs give particular attention to details. Then No. 19, (Ratha Jatra Car. 1929), No. 20, (Calcutta. 1932) and No.21, (Cats Palace reflections, Mahishadal) show Daddy’s unique ability to use trees and nature to compliment manmade structures.

(17)

Street view, Calcutta. 1921. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(17)

Street view, Calcutta. 1921. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(18)

A crowd of bathers. 1922. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(18)

A crowd of bathers. 1922. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(19)

Ratha Jatra Car. 1929. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(19)

Ratha Jatra Car. 1929. Glass Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(20)

Calcutta. 1932. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(20)

Calcutta. 1932. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(21)

Cats Palace reflections, Mahishadal. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(21)

Cats Palace reflections, Mahishadal. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

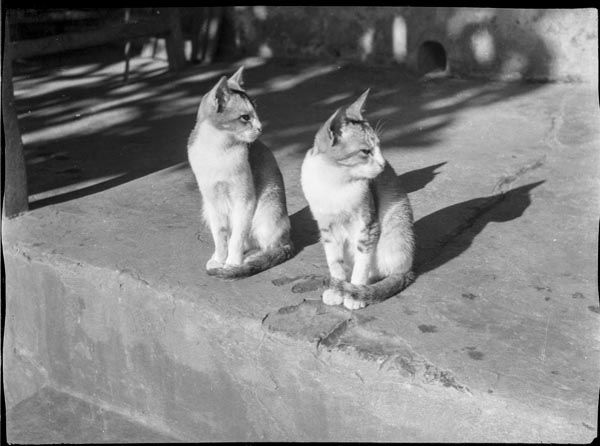

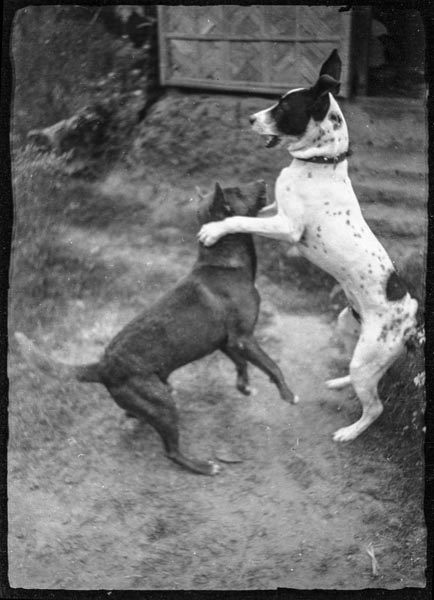

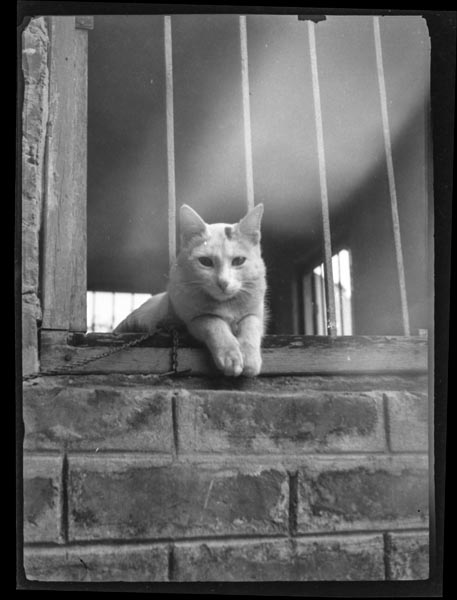

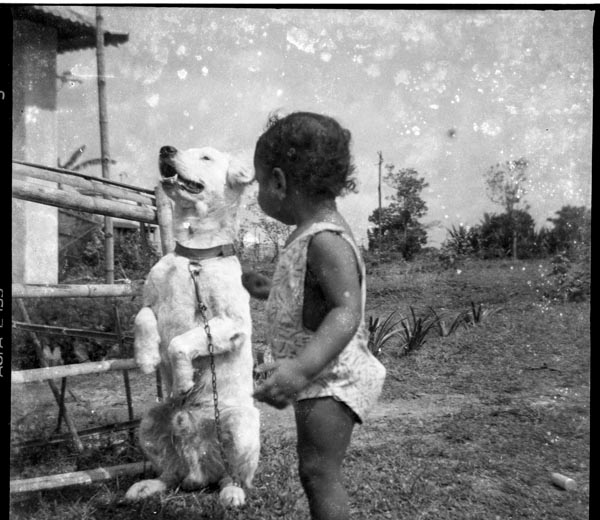

‘Animals – Pet animals like cats and dogs are good subjects for photography. They naturally offer some nice poses and the photographer should be on the alert for this. Cats are a little more difficult as they shift their position unexpectedly just at the time of releasing the shutter. And sometimes they leave their position altogether which may annoy the photographer.

‘Small animals like cats and dogs should be taken from a low angle.’ (SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Golam Kasem Daddy)

Time and again animals appear in Daddy's photographs, sometimes as part of the background, and sometimes as co-subjects or main subjects. No. 22, (Lady with her dog. 1928) and No. 26, {Friends (children with dog) Dhaka. 1948} are photographs taken 20 years apart that show the same love and bond with human beings and dogs. While No. 23, (No caption), No. 25, (Playful dogs, Dhaka. 1950) and No.25, (Expectant cat, Dhaka. 1950) show Daddy’s ability to capture these animals in decisive moments.

‘Small animals like cats and dogs should be taken from a low angle.’ (SIMPLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Golam Kasem Daddy)

Time and again animals appear in Daddy's photographs, sometimes as part of the background, and sometimes as co-subjects or main subjects. No. 22, (Lady with her dog. 1928) and No. 26, {Friends (children with dog) Dhaka. 1948} are photographs taken 20 years apart that show the same love and bond with human beings and dogs. While No. 23, (No caption), No. 25, (Playful dogs, Dhaka. 1950) and No.25, (Expectant cat, Dhaka. 1950) show Daddy’s ability to capture these animals in decisive moments.

(22)

Lady with her dog. 1928. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(22)

Lady with her dog. 1928. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(23)

No caption. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(23)

No caption. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World (24)

Playful dogs, Dhaka. 1950. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(24)

Playful dogs, Dhaka. 1950. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(25)

Expectant cat, Dhaka. 1950. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(25)

Expectant cat, Dhaka. 1950. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(26)

Friends (children with dog), Dhaka. 1948. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(26)

Friends (children with dog), Dhaka. 1948. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

‘But every cloud has its silver lining, and I had mine. Though I had failures, I found inspiration from works of famous photographers like Bourne and Shepherd, Johnston and Hoffman, and female photographer Edna Larange.

‘In spite of frequent failures, I persisted, and by dint of diligence and strong determination, I gradually made progress. I began photography with a quarter size Ensign Box Camera (taking plates only), and made progress through folding film cameras of Kodak, Agfa, Voigtlander, Zeiss Ikon, etc and Twin Lens Reflex cameras, like Minolta, Yashica, Olympus, Nikon, Canon etc.

‘I have used hundreds of cameras of different types, from cheapest to the most costly, and I am of the opinion that the cheapest cameras will produce good results with proper care, but costly cameras will give bad results if not correctly used. So, those who cannot afford costly cameras should not grumble.

‘As I had to learn photography with great difficulty I decided that I would devote the rest of my life to imparting the knowledge of photography to others. And as a result, the Camera Recreation Club was founded in 1962.’ (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90)

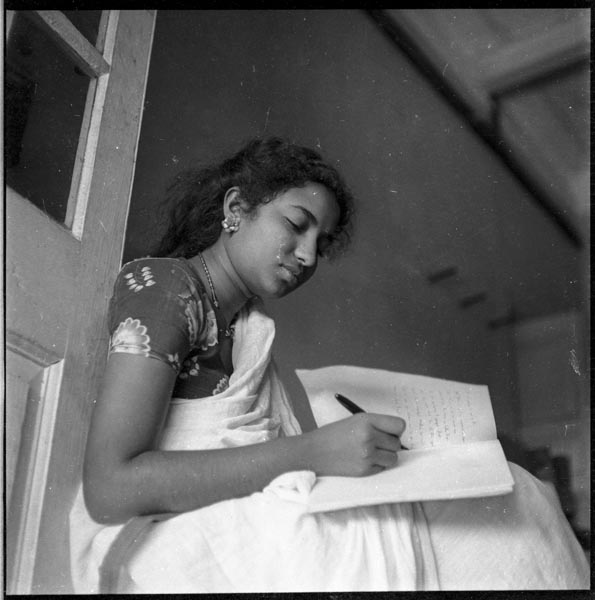

These four photographs are portraits of women taken during the early to mid 1900s in a different and positive light. No. 27 (Woman fishing, Kukrahati, Midnapore. 1922) in fact breaks some norms, as the lady is not only fishing but also wearing a Bicha (Waist Chain). The glass negative has cracked like a net, giving this image a different atmosphere. Then No. 29, (Engaged in writing. 1952) is a one of a kind in terms of composition and view point. Both the photographs tell the story of independent women. No. 28 (Cooking. 1950) and No. 31(Cooking, Midnapore. 1936), taken 14 years apart, show women carrying on with their daily life. At this period of time, the photographs of women in this area rarely showed this aspect of life. These images are rare windows to the past, of a time long lost.

‘In spite of frequent failures, I persisted, and by dint of diligence and strong determination, I gradually made progress. I began photography with a quarter size Ensign Box Camera (taking plates only), and made progress through folding film cameras of Kodak, Agfa, Voigtlander, Zeiss Ikon, etc and Twin Lens Reflex cameras, like Minolta, Yashica, Olympus, Nikon, Canon etc.

‘I have used hundreds of cameras of different types, from cheapest to the most costly, and I am of the opinion that the cheapest cameras will produce good results with proper care, but costly cameras will give bad results if not correctly used. So, those who cannot afford costly cameras should not grumble.

‘As I had to learn photography with great difficulty I decided that I would devote the rest of my life to imparting the knowledge of photography to others. And as a result, the Camera Recreation Club was founded in 1962.’ (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90)

These four photographs are portraits of women taken during the early to mid 1900s in a different and positive light. No. 27 (Woman fishing, Kukrahati, Midnapore. 1922) in fact breaks some norms, as the lady is not only fishing but also wearing a Bicha (Waist Chain). The glass negative has cracked like a net, giving this image a different atmosphere. Then No. 29, (Engaged in writing. 1952) is a one of a kind in terms of composition and view point. Both the photographs tell the story of independent women. No. 28 (Cooking. 1950) and No. 31(Cooking, Midnapore. 1936), taken 14 years apart, show women carrying on with their daily life. At this period of time, the photographs of women in this area rarely showed this aspect of life. These images are rare windows to the past, of a time long lost.

(27)

Woman fishing, Kukrahati, Midnapore. 1922. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(27)

Woman fishing, Kukrahati, Midnapore. 1922. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World (28)

Cooking. 1950. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(28)

Cooking. 1950. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World (29)

Engaged in writing. 1952. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(29)

Engaged in writing. 1952. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World (31)

Cooking, Midnapore. 1936. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(31)

Cooking, Midnapore. 1936. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World‘In my last days of life, I am very glad to see the progress of photography in Bangladesh. It is really surprising that photographers of Bangladesh could secure international fame in face of enormous difficulties. This has been possible due to their indomitable diligence and perseverance only.

‘It seems the day is not far off when Bangladesh will be closely and agreeably related to other nations of the world through photography.

‘Before I close this sketch, I wish all photographers of Bangladesh better photography, long life and prosperity.’

Golam Kasem (Daddy) (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90)

‘It seems the day is not far off when Bangladesh will be closely and agreeably related to other nations of the world through photography.

‘Before I close this sketch, I wish all photographers of Bangladesh better photography, long life and prosperity.’

Golam Kasem (Daddy) (A Short Sketch of My Photographic Life, Date: 28.1.90)

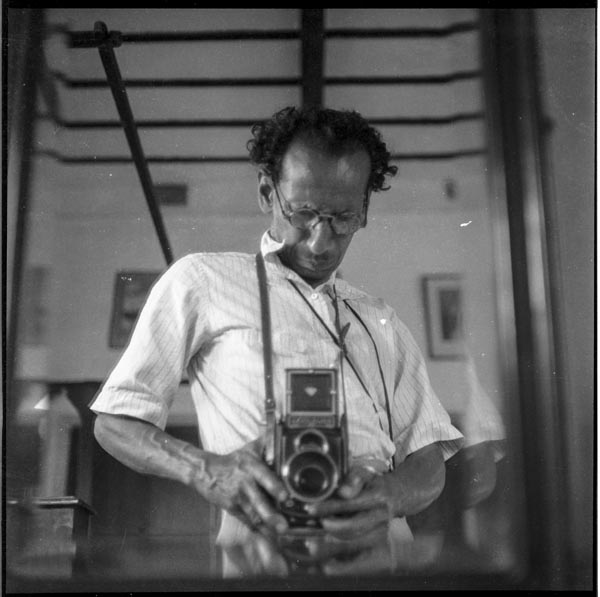

(31)

Photographer at work. 1951. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

(31)

Photographer at work. 1951. Negative. © Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority WorldA selfie of our era but a self-portrait of Daddy’s time. No. 31, (Photographer at work. 1951), with its caption, informs us that the identity of being a photographer was very important to Daddy. This is one of my favorite photographs by Daddy; as one can visibly see the strong-willed man: independent, focused and never compromising.

What makes Golam Kasem Daddy different from other photographers, is a very thin line of being a father. To my knowledge he never had any biological children; a fact possibly allowed him to be different. Since he was not entangled by parenthood, he allowed himself to become Daddy to all of us. A selfless love for photography and a willingness to see his legacy be carried on by photographers in the years to come. Daddy’s achievement is us: he lives in our successes, our existence. Like heirlooms, we the Bangladeshi photographers carry the name ‘Daddy’ in our souls.

My heartfelt gratitude to Drik, for their preservation of and access to the archive of Golam Kasem Daddy. It was an honor for me work on this master photographer’s archive.

What makes Golam Kasem Daddy different from other photographers, is a very thin line of being a father. To my knowledge he never had any biological children; a fact possibly allowed him to be different. Since he was not entangled by parenthood, he allowed himself to become Daddy to all of us. A selfless love for photography and a willingness to see his legacy be carried on by photographers in the years to come. Daddy’s achievement is us: he lives in our successes, our existence. Like heirlooms, we the Bangladeshi photographers carry the name ‘Daddy’ in our souls.

My heartfelt gratitude to Drik, for their preservation of and access to the archive of Golam Kasem Daddy. It was an honor for me work on this master photographer’s archive.

Copyright of the photographs belongs to Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World. Any part of this article cannot be used without the written permission of the author.