Bijan Sarkar: Illuminated dispositions

/ Shadman Shahid

“I could write about Bijan Sarkar. I used to be a fan of his”. A feeling of overwhelming guilt came over me as I uttered these two sentences to Shamim, as if I had voiced blasphemy; I had sinned. I think it was the words “used to” that brought about the guilt; they can stink like death from time to time. I used to be a photographer, I used to love making art, I used to be curious, passionate, experimental. “Used to” can be the most self-confronting words in the English language. Or maybe, there was a guilt in recognising the distance - in time, space, culture, language, urgencies - between me and Bijan Sarkar. Don’t let my theatrical confessions mislead you, though; I am not depressed. There is a form of bliss in the safe, mundane familial life here in Europe that I can absolutely appreciate. But that comes at a high personal cost, which I cannot ignore.

The task of writing about Bijan Sarkar felt like trying to speak about a lost love who you haven’t met in years, and in all honesty, can’t remember if you have ever met them at all. “By the way! I have a photograph made by him that I am sure you haven’t seen before. But you have to promise to keep it secret. For your eyes only. I am sending it to your WhatsApp.” Said Shamim, the wise librarian. As I looked at the photograph, all of my synapses went off all at once, and I was flooded with old memories.

The task of writing about Bijan Sarkar felt like trying to speak about a lost love who you haven’t met in years, and in all honesty, can’t remember if you have ever met them at all. “By the way! I have a photograph made by him that I am sure you haven’t seen before. But you have to promise to keep it secret. For your eyes only. I am sending it to your WhatsApp.” Said Shamim, the wise librarian. As I looked at the photograph, all of my synapses went off all at once, and I was flooded with old memories.

© Bijon Sarkar

© Bijon SarkarI was first introduced to his work about 14 years ago, in Pathshala room number one. Back then, the place didn’t have the shine that the new building has now, and it wasn't fitted with the same bells and whistles, but the place was sodden with magic. Materially speaking, there might not have been much. There were two and a half classrooms; the half was called the multimedia room (not sure why that room was more multimedia than the others, but we will let that be). It could barely fit all of us during classes, so we would have to squeeze in, half of us seated on chairs, the rest sitting or lying on the floor, some maybe on the laps of their comrades. There was a tiny library where only the very serious students would go, or those of us who were in desperate need of a nap. There was a darkroom for the enthusiasts and secret lovers. A computer lab where Munir bhai taught us the difference between JPEG and TIFF, among other things, of course. And the “smoking zone”, where people from all corners of the world engaged in intellectual (and at times quite un-intellectual) dialogue and debates about art, life, politics and photography. Mostly photography. And all of this happened in the presence of the wise mango tree, who looked after us and the many who came before us. Pure magic that place was.

So there I was in this place of magic, fresh out of my one-year hiatus from society. A bright-eyed, naive romantic, a rebel without a cause, sitting in room number one, waiting to be educated about the history of photography by Tanzim Wahab, equally bright-eyed, not-so-naive romantic, a rebel with clarity. Any man with less love for photography than Tanzim would have made the course a very dull affair. I mean, how many white male photographers, obsessed with the rule of thirds, golden light, symmetry and other antiquated, appropriated laws of composition from their painting history, can one look at with any seriousness? Decisive moments, f64, secessionists blah blah blah, are important thoughts in photography, I guess, but it’s hardly sustenance for the adventurous soul that wants more than tired cliches and impoverished representations. Then appeared Bijan Sarkar in the picture, like the water from the Zamzam well, to soothe the suffering of those of us who were parched.

© Bijon Sarkar

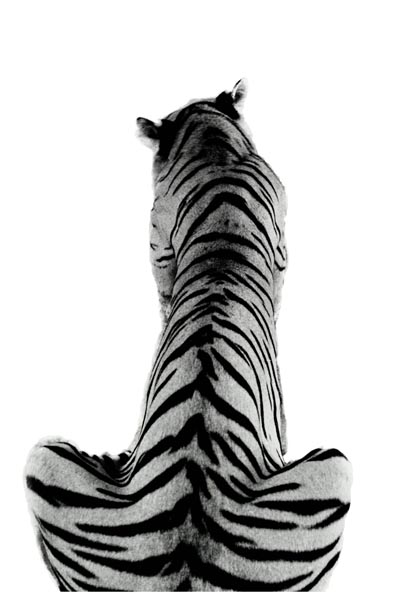

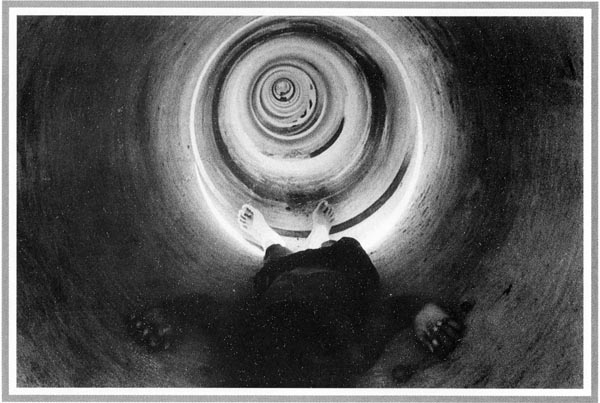

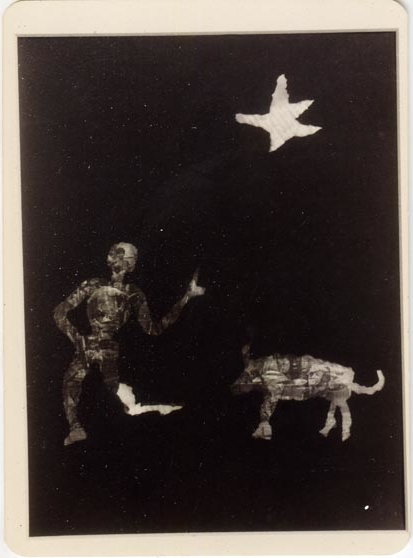

I still remember the moment vividly. There was an image projected on the wall. Massive, life-sized. A tiger facing away from the camera, its shape and the stripes on its back standing out in stark contrast to the whiteness of the background, not totally white but like being blinded by the light. Like in a void. Next picture. A child’s body falling down a vortex. Rings of light and shade creating an illusion of endlessness. My eyes spiralled down to follow it. Next picture. Two figures. Revolutionaries holding guns. A woman and a man. Two-dimensional, looks as if it is a paper cutout. A photograph made without a camera. A photogram? I was completely mesmerised. Not because I was swept away by the technical brilliance (which was obviously there), but for a more visceral, instinctual reason that is hard to pin down with words. The connection could even have been spiritual, perhaps? As I was thinking I had never seen anything like this before, some annoying little know-it-all proclaimed with a smirk, “He wants to be Man Ray”. I shot at them a killer look of disagreement. Tanzim had shown us Man Ray, already among other surrealists, a few weeks earlier. If one only looks at the surface of the photograph, there can be lots of similarities found in terms of techniques, but that is deceptive. In actuality, the two photographers are worlds apart. Looking is not enough; you have to gaze into the photographs to know for yourself.

© Bijon Sarkar

It is hard not to compare Bangladeshi photographers with Western photographers, perhaps mainly because photography was invented in the West. But since its inception, photography has had different definitions in different languages that fundamentally change the essence of the medium. In Bangla, a photograph is called “Alokchitro”: “Alok” can mean light or illumination and “chitro” means a small representation, so together it means an illuminated small representation. And photography in Bangla can be “Alokchitro Shilpo” (or“Alokchitro Bidya” or “chobi tola”. There can be multiple translations depending on the context. For our context, Alokchitro Shilpo is most appropriate.) The word “Shilpo” can mean art or artistry—so photography in Bangla is the art of making illuminated small representations. Whereas the English word “photography”, as you know, is drawing with light from the Greek words phos and graphe. Undoubtedly, there are similarities between the two definitions of the medium, most significantly the acknowledgement of light, which in turn, refers to the “how” of the matter. The “what”, however, differs essentially. In Greek/English terms, “what” is produced is a drawing or writing made with light, through the act of drawing or writing with light. Whereas, in Bengali terms, what is produced is illuminated small representations made through artistry and therefore what is produced is by default art. Where the English term creates an offshoot or a replica of existing forms of expression (Drawing and writing), the Bangla term creates an original art form, free from the shackles of what came before, with freedom to create its own identity.

© Bijon Sarkar

Similarly, for me, when we compare Bijan Sarkar to Man Ray, the “how” may be similar, but the “why” is fundamentally different. The difference lies in intention and outlook, perspective and function, in expectation. When I look at Man Ray, I am reminded of the West’s obsession with naming things, its insatiable need to define and control. It reminds me of the colonial practice of categorising to dominate. Names such as surrealism, dadaism and other “isms” that feed into the “aura” of the artist more than anything else. Whereas, in Bijan Sarkar’s work, the act of making, the art, takes priority. The practice comes firs and foremost, total dedication to his craft, to the point of worship, shadhona, that’s what drives him, that’s why he photographs. He says so in his interview with Munem Wasif, which was published in Kamra volume 1. He learned about shadhona at a young age from his much older artist brother, and that has been his purpose ever since. He speaks about his reluctance to look at Western photography, priding himself on not knowing the superstars of his time, keeping his imagination as untainted as possible. He knew photography intimately, finding the depths of it through exploration and practice, not relying on others' descriptions of it. That’s what I see when I gaze upon his work, completely mesmerised. An originality that is defiant in the face of the monotonous normalisation of predictability.

© Bijon Sarkar

Bijan Sarkar’s legacy had a profound impact on me and many like me. He taught me about courage, the kind that comes by prioritising knowing over glory. About quiet confidence that comes from an unwavering dedication to one's craft and practice. He taught me to be comfortable in my own perspective of the world and not rely on others' interpretations of it. It is said that photographs capture the soul of their subjects. He showed me that some photographs are infused with the soul of the maker, but only when their shadhona is at its peak. Those photographs are the most special, and out of the trillions of images we see over our lifetime, those are the ones that stay in our memory.

My memory of him had been locked away in a faraway corner of my consciousness somewhere, collecting dust. Perhaps that’s where my guilt also comes from. The fact that I failed to adequately care for something so precious, and as a result, a big chunk of my being went missing, and in its place a void festered. The photograph Shamim shared reprimanded me and put me on the path of restoration. That’s what some photographs can do. They hold within them the potential to transport you through time and space. To move you, your conscience, your state of being. To transform you.

I remember now. I did meet him once, in Drik. Right before he passed away. He was looking at an exhibition, dressed in all white, a small white bag by his side. I darted towards him and fell to his feet. He looked completely befuddled. He asked, “Why do you prostrate to me?” Equally befuddled, I replied, “What else should I do?”

My memory of him had been locked away in a faraway corner of my consciousness somewhere, collecting dust. Perhaps that’s where my guilt also comes from. The fact that I failed to adequately care for something so precious, and as a result, a big chunk of my being went missing, and in its place a void festered. The photograph Shamim shared reprimanded me and put me on the path of restoration. That’s what some photographs can do. They hold within them the potential to transport you through time and space. To move you, your conscience, your state of being. To transform you.

I remember now. I did meet him once, in Drik. Right before he passed away. He was looking at an exhibition, dressed in all white, a small white bag by his side. I darted towards him and fell to his feet. He looked completely befuddled. He asked, “Why do you prostrate to me?” Equally befuddled, I replied, “What else should I do?”

Copyright of the photographs belongs to Bijon Sarker. Any part of this article cannot be used without the written permission of the author.